Research indicates that queer, lesbian and bisexual women are at greater risk of a number of health, mental health and psychosocial problems including:

History of childhood and adulthood sexual assault in their lifetime, as well as in the context of romantic relationships, compared to gay and bisexual men. (Rothman, Exner, & Baughman, 2011).

Asthma, obesity or a high , arthritis, and cardiovascular disease, lower ratings of overall health, than their heterosexual counterparts.

Higher daily smoking and higher rates of alcohol consumption than heterosexual women.

Breast cancer, although there are limited studies that report on the actual numbers of queer women suffering from such condition. Risks for cervical cancer, particularly for bisexual women, have also been estimated as considerably high, although information is also limited on this subject.

Factors related to minority stress can account for these health disparities.

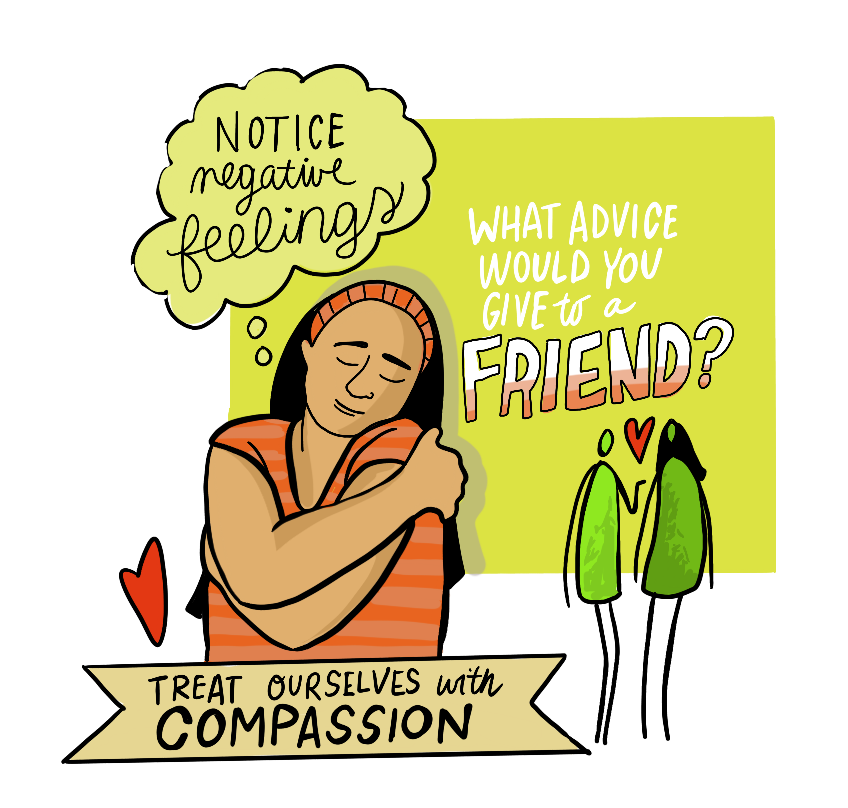

Accounts of resilience in the face of adversity in sexual minority women are also abundant. Through engaging in collective action and self-advocacy, cultivating supportive friendships and family relations, creating safe places and joining their community, and embracing their identity, can help them better face the effects of stigma and discrimination.

The following are examples of sexual minority women’s testimonies of experiencing discrimination and coping with stigma:

“And ever since I opened up that closet there’s been family members that have been trying to put me back in the closet. There’s been people that’s been in my corner saying, ‘Look, you’ve got to live your life for who and what you are and don’t worry about what people think.’ So I’m at the point in my life where I’m not caring about what people think. I’m a person that beat to the beat of my own drum. I’ve always been that, so why wouldn’t my sexuality be like that as well? I am defined by a Black lesbian woman that I am. And it’s not an easy thing to be because the majority of people don’t like me because of my choice but I can’t worry about what people think.”

(African-American, lesbian, age 51) (Drabble et al., 2018)

“And I sort of pulled away from everybody somewhat when I started to realize my sexuality because I was kind of scared and not sure of the acceptance, which I think is fairly common. But once I came out and they went through what they needed to go through, everything is fine.”

(White, lesbian, age 54) (Drabble et al., 2018)

“So I’m very close to my mom, though we had a brief period in my early twenties when we had a bit of a rift when I came out as bisexual, but we are very close again, so it’s just she had some struggles around that.”

(White, bisexual, age 42) (Drabble et al., 2018)

“Yeah, I have—since I’m a recovering alcoholic and addict, I think I’ve started to really develop social connection and relationships after I got in recovery. When I got into recovery, you begin to share with people who have been and had your similar experience. But that’s where I learned about give and take, support and getting support. I mean, that is an incredible—I consider it a good thing that happens to those in recovery. We begin to learn how to do those things with people.”

(White, lesbian, age 64) (Drabble et al., 2018)

“It was until I was 30 that I was closeted. Then at 30, which is almost 40 years [...] I became aware that, oh, my goodness, there were other people like me, and that was fun. [...] And, you know, every one of those people, just like me, have a story to tell, and there’s pain in every one of those people’s stories, loneliness, hesitancy in coming out, not so hesitant, sickness, AIDS, on and on and on. And I just thought, wow. No reason to feel alone anymore.”

(White, lesbian, age 67) (Drabble et al., 2018)

“ had a picture on Facebook kissing my girlfriend, and my aunt saw it and she didn’t like it. She had told me that her daughter, she was like two years old at the time, that she saw it and she asked her what it was and she didn’t wanna tell her. Well now, she’s more accepting of it and now she tells her daughter that it’s something of love because I had explained to her previously that it’s not like I’m killing her, I’m showing affection and love to her, it’s not like I’m slicing her throat or something, so . . . I explained to her in a good manner and said that instead of telling her it’s something bad she could have told her daughter that it’s something loving and something positive, not a negative.”

(Claudette, age 18, Haitian, bisexual) (Craig et al., 2017)

“I think like it opened like I had a closer bond with my mom because now I told her the truth and it made our bond stronger and we could get along more and the thing is that when it comes to my sister since it’s more open now she’s like gay everyone accepts her more.”

(Yvonne, 18, mixed race, lesbian) (Craig et al., 2017)

“[I]f I can’t take it anymore in my house and I can’t go to the gym and I can’t do anything else I’ll call up my friend and then we’ll go, and then I’ll come back home and they’ll still be going at it and I would just feel like okay and not as worried . . . .

(Patrice, 17, Haitian, bisexual)” (Craig et al., 2017)

“. . . lesbians have the potential to have a greater understanding and analysis of that whole idea of other, and being a member of an oppressed group. . . . [E]ven lesbians who . . . aren’t survivors of abuse, . . . seem to have some level of support and tolerance and compassion, that I think sometimes heterosexual women don’t have.”

(Baker, 2003)

“I joined a care group . . . with lesbians only. . . . [T]he image that comes to mind is a cocoon. The church cannot give you everything. . . [In the care group] there was a lot of phone support between the women, and there I talked about my incest.”

(Baker, 2003)